Dear friends,

Our new film Observer is finally at its first rough cut stage. This means the film is vaguely watchable all the way through. So I watched it. I watched it in the bagel shop in town, on my laptop with my headphones on. If possible, I like to get a bagel with olive cream cheese, because when I was a boy, now and again a sandwich would appear on Pepperidge Farm white bread with cream cheese and chopped green olives. I don’t know what you call a sandwich like that. The coffee at the bagel shop is unremarkable, but really any caffeine will do, it has to power you through about 105 minutes of rough footage.

Because we’re not at a polishing stage, a noisy bagel shop is okay. I like having people around. It’s easier for my mind to make the leap to wondering what they - the assorted customers at a bagel shop in Maine, carpenters, financial planners, retirees, weary farmers, a Dad with a baby, Lewis Wheelwright - would make of what I’m watching. Floating those two things in the mind at the same time is key: what do I make of this, and what will others make of this?

The caffeine is helpful because the default emotional response to a rough cut is despair. Caffeine deludes the filmmaker into thinking the cut is in pretty good shape, which allows one to get through the whole thing without pouring coffee and olive cream cheese into the laptop and throwing it in the river. (The new location of the bagel shop is convenient to river tossings.)

One puzzle is whether to take notes or not. Ideally you can watch the film twice. First, you take no notes, you just watch. That way you immerse and don’t miss anything. I’ve sat with humans who take really long notes, hunching over to scribble a paragraph of text only to look up having missed several minutes of the film. When the credits roll they want to know why X or Y was cut from the film, when in fact they just missed it. Tolerating this idiocy tests my limits.

But sitting for 2 x 105 = 210 minutes in the bagel shop to watch a film twice through is not an acceptable way to spend a morning in Maine, so these days I watch it once, and take shorthand notes. Over the years I’ve developed a set of symbols that I can use. Most of them relate to the fact that an editing timeline is a linear array of rectangles splayed out running from left to right. To edit you move these rectangles around in different configurations. (Filmmaking is glorious!) Many of my symbols refer to nudging things left or right, extending them or tightening them, or cutting them out entirely. I also try to note moments that don’t need to change, but instead embody the way the film should be, a moment where things are really dialed in.

I’m spending most of the time sizing up the scenes. Few are in the shape they’ll be in in the final film. So you have to watch them with an eye towards what they might possibly be. The sound is still rough, the cuts are still jumpy, but you have to figure out whether the idea is right, whether something has the potential to work. When I was first getting started in filmmaking, I was terrible at judging this. Either I had too much confidence that a bad scene could work, or I discarded a bad scene too readily. I still get blinded sometimes by my own biases - this footage was so hard to get, I just know it will work! - but over the years I’ve grown a little better at knowing when to hold ‘em and when to fold ‘em.

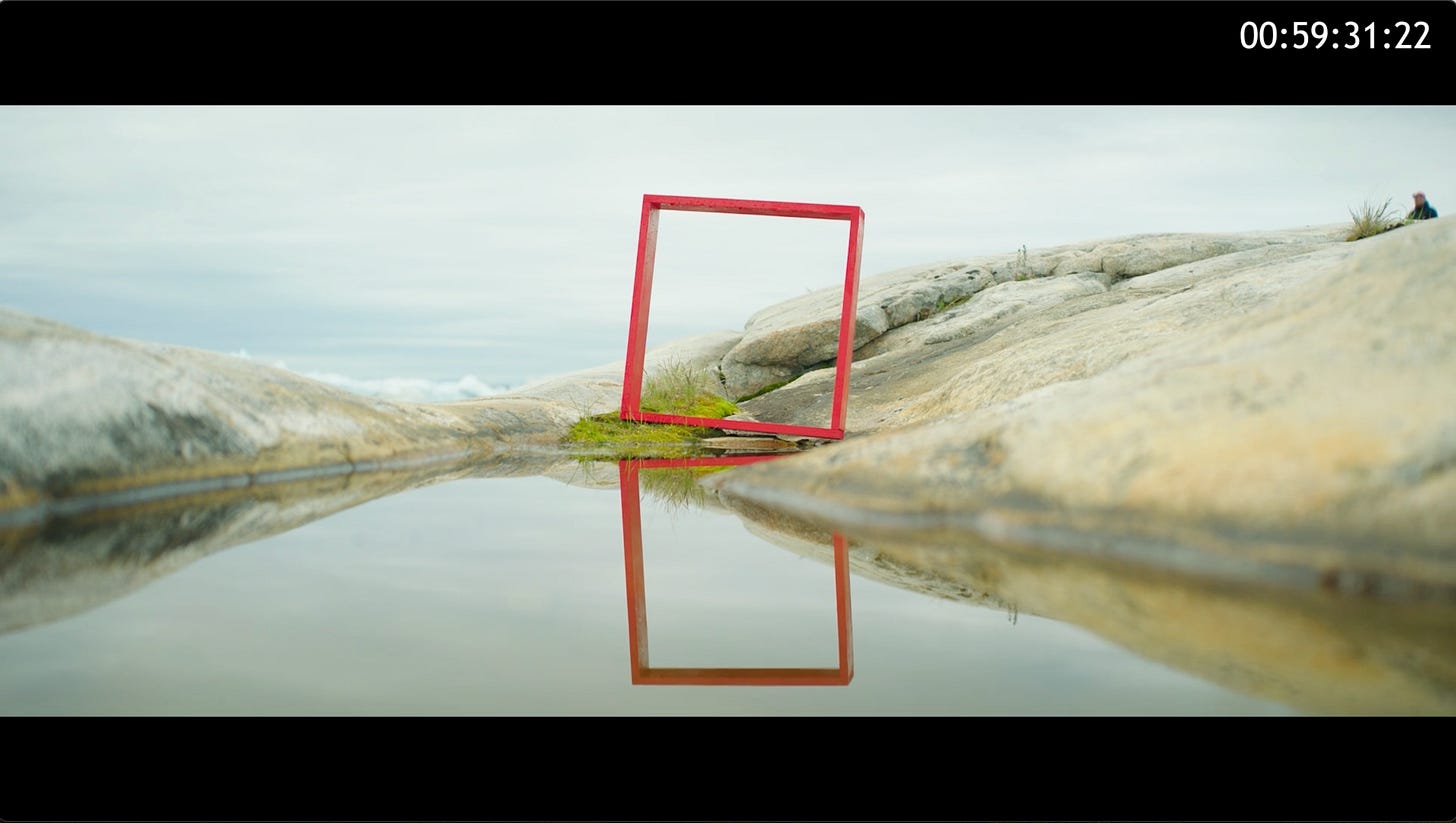

Then there’s the matter of whether the film as a whole is working. For a film like Observer, this is a mysterious goalpost, because the film isn’t setting out to prove a thesis or tell one particular story. It’s an exploration of observation, and an invitation to the audience to understand more deeply what it’s like to see like a scientist, or an artist. What the final film should feel like as a whole is unknown. Complicating the matter is that everyone will see the film differently. No two people will see it the same way. That’s inherent to humanity, focus groups say what they will. So even if I arrive at a place where I’m happy with how the film feels to me as a whole, will I be happy with how it feels to others? And which others?

In these moments I remember despairingly that my tastes are not trustworthy. I haven’t seen most of the TV shows and movies that most people have seen & liked, not because I’m spending my time doing better things but just because I’m one of those people who, time and again, doesn’t seem to have a clue. If I’m clueless about pop culture and mainstream tastes, then is it bad if I end up liking a rough cut? Bad for success by conventional measures, perhaps. This isn’t true crime or celebrity drama. But bad for me, for an audience, for the world?

Which is all a way of saying that when you’re watching a rough cut, you’re also puzzling through the impossible question of what success looks like — in this film, in the life of the filmmaker, in the life of a human. How annoying! You take another bite of bagel, and wonder if there are olives in this cream cheese after all.

Love the insights into your editing process!

Ahh this is one of your best newsletters ever. Olive you!